Ashoka's Inscriptions - Major Rock Edict I

How hard is it to read the oldest decipherable inscriptions found in India?

Ashoka (ruled c. 268-232 BCE), the third Mauryan emperor, ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent for almost four decades. Early in his rule, he waged an intense war against the kingdom of Kalinga in eastern India (modern-day Odisha), and eventually won. But the brutality of that war made him have a change of heart, leading to his adoption of Buddhism. During his long reign, he dedicated himself to promoting peace and justice across his empire.

As part of his mission, he commissioned stone inscriptions all across his empire. Today, these are classified as the major/minor rock edicts, and the major/minor pillar edicts. The edicts are largely instructions to citizens on how to live ethically, emphasizing religious tolerance between Brahmanas (Brahmins) and Shramanas (Buddhists/Jains). They also reveal some of the emperor’s thoughts about himself and his rule.

Ashoka’s edicts are the oldest known inscriptions found in India, apart from the symbols on the Indus Valley tablets, which have not yet been deciphered (and which, as some scholars now think, may not even represent a language). That’s right - between the Indus Valley Civilization (ended c. 1500 BCE) and Ashoka (200s BCE), there is no surviving evidence of writing in India! The edicts are mostly written in Brahmi script, which was no longer legible to Indians when the British were discovering the edicts in the 19th century. The script was deciphered by James Princep, leading to a “rediscovery” of Ashoka, who at the time was basically only remembered by Buddhist scholars outside of India. Today, Ashoka is seen as a major figure in Indian history, symbolizing powerful yet ethical rule. His lion capital is the emblem of the modern Indian state.

The various versions of the edicts, distributed by the emperor across the subcontinent, are written not in Sanskrit, but in regional Prakrits. The linguistic variations of the edicts in different parts of India reflect the local Indo-Aryan dialects that existed in these regions at the time. By comparing the language of edicts in different regions, historical linguists can improve models of language change across India.

Let’s explore what you need to know in order to read and understand the inscriptions directly (i.e. from photographs of the actual stones). In the first section, we will acquaint ourselves with the Brāhmī script, which, like modern Indian scripts, is an abugida, represents the sounds found in Sanskrit, and is read left-to-right. After that, we will be able to read out the inscriptions phonetically, but still need to figure out what it means. In the second section, we will translate the Girnar version of Major Rock Edict 1 word-for-word, relying Inscriptions of Asoka, an extensive text by Eugen Hultzch, a German indologist who worked in British India in the late 19th century. If you already know some Sanskrit, the language of the edicts will start making sense once you see the English translations (kind of a similar experience to trying to read Dutch if you already know German). In the third section, while I won’t attempt to systematically discuss the language of the Girnar Prakrit (for that, you can read the Hultzch book), I will point out some features that I found interesting.

The Brāhmī script

As the first known example of post-Harappan writing in India, the Ashoka edicts are also the first example of the Brahmi writing system. Although details about its origin are unclear, there seems to be consensus that it was probably derived from Aramaic script, which diffused into India via the Persian Achaemenid Empire. What is not known is if it existed for some time (i.e. decades/centuries) prior to Ashoka, or if Ashoka had it developed specifically for his inscriptions. Most of the scripts used to write the modern Indian languages (both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian) are derived from Brahmi, having evolved through various historical scripts which have since fallen out of use.

A very useful (free) online tool for both learning and typing in Brahmi is Lexilogos (they also have typing tools for a lot of other ancient and modern languages). If you go to the website, there is a box where you can type out words phonetically and it will automatically transliterate into Brahmi. They have a succinct table of the characters:

Brahmi works like other Indian writing systems which descend from it. It’s an abugida (alphasyllabary), with characters for consonants and vowels. The consonant characters are by default followed by the vowel ‘a,’ and are augmented with diacritics to generate other syllables. The sounds being represented are basically the same as in Sanskrit.

Translating the Major Rock Edict 1 (Girnār version)

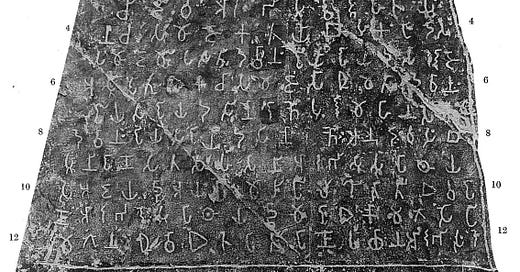

Here is a photograph of the top part of the stone inscription from Girnār in modern-day Gujarat. It corresponds to Major Rock Edict 1.

Let’s dive into translation line-by-line! In what follows, the Brahmi characters are first reproduced in clear digitized form using Lexilogos. Note that the form of the diacritic ligatures here will not always correspond exactly to the actual inscriptions, since this online tool is most likely a standardization/simplification of different variants of Brahmi. Below the Brahmi will be a transliteration into Devanagari, its distant descendant. I debated transliterating into Roman but decided against it, because I thought it would be interesting to visually juxtapose the forms of Brahmi and Devanagari. So if you can’t read Devanagari, learn that first! Lastly, the English translation of each word is provided below the transliteration. I have tried to keep it as literal as possible, so for example a noun “X” in genitive case will be translated as “X-of” instead of “of X,” etc.

For the transliteration and translation, I am referring to Hultzch p. 1. Following the convention there, each line in the stone is indicated with a numeral (1-12), while each sentence (which may run across multiple lines) is indicated with a Roman letter (A-H). There is no indication of word- or even sentence-breaks in the original inscription; all the letters are basically evenly spaced out across the entire thing!

(Note: the following text will probably only be correctly aligned when viewed on Desktop)

1) 𑀇𑀬𑀁 𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀻 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑁆𑀭𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 इयं धंमलिपी देवानंप्रियेन (A) this ethics-writing gods-of-beloved-by

2) 𑀧𑁆𑀭𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀭𑀸𑀜𑀸 𑀮𑁂𑀔𑀸𑀧𑀺𑀢𑀸 𑀇𑀥 𑀦 𑀓𑀺𑀁

प्रियदसिन राज्ञ लेखापिता इध न किं-

Priyadarshi-by king-by written (B) here not any- 3) 𑀘𑀺 𑀚𑀻𑀯𑀁 𑀆𑀭𑀪𑀺𑀧𑁆𑀢 𑀭𑁆𑀧 𑀚𑀽𑀳𑀺𑀢𑀬𑁆𑀯𑀁

-चि जीवं आरभित्प प्रजूहितव्यं

such life killed [or] sacrificed-should. 4) 𑀦 𑀘 𑀲𑀫𑀸𑀚𑁄 𑀓𑀢𑀬𑁆𑀯𑁄 𑀩 𑀳𑀼𑀓𑀁 𑀳𑀺 𑀤𑁄𑀲𑀁

न च समाजो कतव्यो बहुकं हि दोसं

(C) not and gathering done-should. (D) much also sin 5) 𑀲𑀫𑀸𑀚𑀫𑁆𑀳𑀺 𑀧𑀲𑀢𑀺 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺 𑀬𑁄 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺 𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺 𑀭𑀸𑀚𑀸

समाजम्हि पसति देवानं प्रियो प्रियदसि राजा

gathering-in sees gods-of beloved Priyadarshi king. 6) 𑀅𑀲𑁆𑀢𑀺 𑀧𑀺 𑀢𑀼 𑀏𑀓𑀘𑀸 𑀲𑀫𑀸𑀚𑀸 𑀲𑀸𑀥𑀼𑀫𑀢𑀸 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁

अस्ति पि तु एकचा समाजा साधुमता देवानं-

(E) is also but some gatherings meritorious gods-of

7) 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺 𑀬𑀲 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺 𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦𑁄 𑀭𑀸𑀜𑁄 𑀧𑀼𑀭𑀸 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀦𑀲[𑀫𑁆𑀳𑀺]

-प्रियस प्रियदसिनो राज्ञो पुरा महानस[म्हि]

love-of Priyadasi-of king-of (F) whole kitchen-in

8) 𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀲 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦𑁄 𑀭𑀸𑀜𑁄 𑀅𑀦𑀼𑀤𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀁 𑀩

देवानं प्रियस प्रियदसिनो राज्ञो अनुदिवसम ब-

gods-of love-of Priyadasi-of king-of everyday ma-

9) 𑀳𑀽𑀦𑀺 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀸 𑀡𑀲𑀢𑀲𑀳𑀲𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀦𑀺 𑀅𑀭𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀼 𑀲𑀽𑀧𑀸𑀣𑀸𑀬

-हूनि प्राणसतसहस्रानि आरभिसु सूपाथाय

-ny animals-hundred-thousands killed curry-for 10) 𑀲𑁂 𑀅𑀚 𑀬𑀤𑀸 𑀅𑀬𑀁 𑀥𑀁𑀫 𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺 𑀮𑀺𑀔𑀺𑀢𑀸 𑀢𑀻 𑀏𑀯 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀸

से अज यदा अयं धंमलिपी लिखिता ती एव प्रा-

(G) but(?) today when this ethics-writing written three only ani- 11) 𑀡𑀸 𑀅𑀭𑀪𑀭𑁂 𑀲𑀽𑀧𑀸𑀣𑀸𑀬 𑀤𑁆𑀯𑁄 𑀫𑁄𑀭𑀸 𑀏𑀓𑁄 𑀫𑀕𑁄 𑀲𑁄 𑀧𑀺

-णा आरभरे सूपाथाय द्वो मोरा एको मगो सो पि

-mals killed curry-for two peacocks one deer that also 12) 𑀫𑀕𑁄 𑀦 𑀥𑁆𑀭𑀼𑀯𑁄 𑀏𑀢𑁂 𑀧𑀺 𑀢𑁆𑀭𑀻 𑀭𑁆𑀧𑀸 𑀡𑀸 𑀧𑀙𑀸 𑀦𑀸 𑀅𑀭𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀭𑁂

मगो न ध्रुवो एते पि त्री प्राणा पछा न आरभिसरे

deer not regularly (H) these also three animals future-in not killedThe English translation given by Hultzch (p. 2) is as follows (footnotes omitted):

(A) This rescript on morality has been caused to be written by king Devanampriya Priyadarśin.

B) Here no living being must be killed and sacrificed.

C) And no festival meeting must be held.

(D) For king Devanampriya Priyadarśin sees much evil in festival meetings.

(E) But there are also some festival meetings which are considered meritorious by king Devanampriya Priyadarśin.

(F) Formerly in the kitchen of king Devanampriya Priyadarśin many hundred thousands of animals were killed daily for the sake of curry.

(G) But now, when this rescript on morality is witten, only three animals are being killed (daily) for the sake of curry, (viz.) two peacocks (and) one deer, (but) even this deer not regularly.

(H) Even these three animals shall not be killed in future.

Some comments on the language

If you know some Sanskrit, a lot of the vocabulary and grammatical forms may seem kind of familiar. For the correspondences with Sanskrit, I refer to the Sanskrit translations of Ashoka’s Edicts found the book Edicts of Ashoka, trans. Murti and Aiyangar. Here are a few points:

devaanam = Skt. devaanaam (‘of the gods’)

aarabhitpa = Skt. aalabhya (‘to be killed’ )

katavyo = Skt. kartavyo (‘should be done’)

dosam = Skt. doSaan (‘evils’)

samaajamhi = Skt. samaajasya (‘of the gathering’)1

pi = Skt. api (‘also’)

tii = Skt. traya (‘three’)

mago = Skt. mRgo (‘deer’)

moraa = Skt. mayuuraaH (‘peacocks’)2

Well, there we have it! We’ve worked through the Girnar version of Ashoka’s Major Rock Edict I, and, in that process, have some knowledge of Brahmi and Prakrit under our belt. In the future, I hope to write some posts about the other Edicts, and also maybe summarize some of the academic work comparing the language at the different sites.

According to Hultzch (p. lxii), -mhi is a locative singular ending, not a genitive form.