Caribbean Hindustani, Pt. II - Translating Chutney Songs

Understanding the lyrics of Sundar Popo's greatest hits

This is the second post in a three-part series on Caribbean Hindustani. In Part I, we studied some grammar basics of this diasporic language, and learned a bit about its history. Now, we will build on this foundation to translate lyrics from famous Caribbean chutney songs. If you like this post, stay tuned for Part III, which will be about the development of Indo-Caribbean pop culture over the last half century.

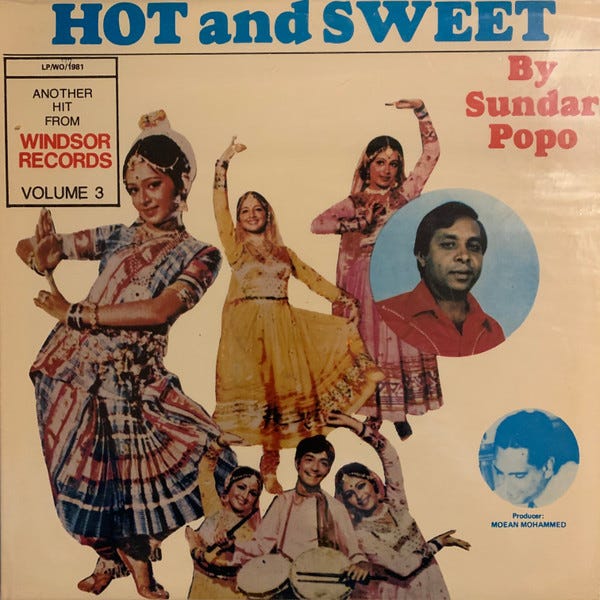

The Indo-Caribbeans, who are the oldest Indian diaspora in the Americas, not only developed their own language (Caribbean Hindustani) but also a new genre of music. Chutney music (named after the spicy-sweet Indian condiment) is a syncretic genre from Trinidad that fuses Indian folk music with elements of Afro-Caribbean calypso. The “founder” of chutney is often considered to be Sundar Popo (1943-2000) with his iconic 1969 hit Nani and Nana (which we will listen to shortly).

What better way to learn about Sundar Popo’s career and the rise of chutney than from the man himself? Here is a great 30-minute episode made in 1999 for a TV program called “Caribbean Insight,” featuring an interview with Popo interspersed with clips of his performances. Popo was born in Trinidad to musician parents who performed traditional songs at weddings in the Indo-Trinidadian community. Drawing from these childhood memories, Popo transformed traditional Indian songs into upbeat dance numbers with electronic instruments. He also composed songs of his own, mixing together English and Caribbean Hindustani lyrics. Chutney gained popularity in the 70s and 80s, which, as we learned in the previous post, coincided with the decline of Caribbean Hindustani in Trinidad. Thus, young people dancing along to these songs would not have understood all of the lyrics, but would have still identified with their “Indian-ness.” In addition to being extremely fun and catchy, the songs of Popo and other chutney artists provide a valuable window into the cultural life of Indo-Caribbeans in the late 20th century, touching on themes such as race and gender relations, as well as ethnic and national identity.

Our primary goal in this post is to achieve a word-by-word understanding of the lyrics of a few of Sundar Popo’s songs. The most relevant grammatical reference will be Peggy Mohan’s 1978 study on Trinidad Bhojpuri, the Trinidadian variety of Caribbean Hindustani. As we will see, however, Mohan’s work cannot account for all of the grammatical features in the lyrics. Thus, we will also rely heavily on S. K. Gambhir’s 1981 work on the closely related Guyanese Bhojpuri. At the end of the post, I will group the grammatical features based on their likely origins, and speculate briefly on how they ended up in Sundar Popo’s lyrics.

To make sure we get the lyrics right, we will restrict ourselves to the songs discussed in a paper by Rajiv Mohabir titled “Chutneyed Poetics: Reading Diaspora and Sundar Popo’s Chutney Lyrics as Indo-Caribbean Postcolonial Literature” (2019). The appendix of this paper features the fully transcribed and translated lyrics of five Sundar Popo songs, and we will examine the first four. Mohabir says that he checked the meanings of the lyrics with his grandmother and her friends and relatives, who were supposedly proficient in Guyanese Bhojpuri (p. 5). Thus, the lyrics and translations he provides should be generally accurate. However, I have taken the liberty to deviate slightly from his transcription and translation in some places.

Nani and Nana (1969)

This appears to be Sundar Popo’s first and most popular song. On YouTube, it has a combined view count (across multiple videos) of over 2.4 million, which is significant when you consider that there are only about 1 million Indo-Caribbeans in total. In the interview, Popo states that this while he had sung “film songs” (presumably Bollywood) prior to 1969, Nani and Nana was his first “local” song, i.e. an original Trinidadian composition.

—Stanza 1—

nānā nānī ghar se nikle, dhīre dhīre caltī hai

nānā (grandfather); nānī (grandmother); ghar se (from the house); nikle (come out); dhīre dhīre (slowly, slowly); caltī hai (walk)

Nana and Nani come out of their house, walking slowly.

madirā ke dukān main, dūno jāke baiṭhehe

madirā ke (of liquor); dukān (store); dūno (both); jāke (having gone); baiṭhe hain (sit)

They both go to the liquor store and sit down.

nānā kine pancin dārū, udhar jaise pānī

nānā (grandfather); kine (buys); pancin (a puncheon); dārū (alcohol); udhar (there); jaise (like); pānī (water)

Nana buys puncheon rum there, as if it was water.

cālis[?] wine aur kilbe[?] wine, karīre merī nānī

cālis[?] wine aur kilbe[?] wine ([two types of] wine); karīre (buys); meri (my); nānī (grandmother)

My Nani buys [two types of] wine.

—Refrain—

āge āge nānā cale, nānī goin’ behin’

āge āge (ahead, ahead); nānā (grandfather); cale (goes); nānī (grandmother); goin’ behin’

nānā drinkin’ white one, and nānī drinkin’ wine

(this is self-explanatory)

—(The remaining lyrics are mostly in English)—

There are a lot of grammatical things going on in these lyrics, reflecting influences from multiple languages. Let’s break them down:

The following stops are pronounced as alveolars by Popo, whereas in Hindi (and other Indian languages) they would be pronounced as dentals: dh in dhīre dhīre, t in caltī, and d in dukān, dūno, and dārū. This sound shift, due to the speakers’ proximity with English, is a distinctive feature of Caribbean Hindustani varieties that is not found in any language back in India. We will observe it again and again in almost all of Sundar Popo’s songs.

The vowel ai in jaise is pronounced like a diphthong (as in Bhojpuri/Maithili/Magahi, as well as Awadhi) rather than the monophthong æ (as in Hindi).

The adjective dūno (“both”) is a Bhojpuri word, common to both the Indian and Trinidadian varieties. The corresponding Hindi word would be dono.

The -e ending on the verbs nikle, kine, karire, cale is probably best understood as a type of Trinidad Bhojpuri 3rd person present tense. Mohan calls this the “present/optative” tense, which can be used in a habitual sense and is distinct from the -lā and -h- present tense forms (Mohan p. 145-146). For Guyanese Bhojpuri, Gambhir calls this use of the [stem]+e construction the “present indicative” (Gambhir p. 224)1. Apparently, this usage is almost completely absent from Indian Bhojpuri, which overwhelmingly uses -lā for present indicative (p. 224-228). Meanwhile, in Standard Hindi, [stem]+e is only used in subjunctive mood (p. 232). Thus, Sundar Popo’s usage of [stem]+e present tense constructions may be considered a distinctly “overseas” Caribbean grammatical feature, somewhat foreign to both Indian Bhojpuri and Standard Hindi.

The song features two verbs meaning “buy”: kine and karire. The former, from the Sanskrit root √krī (as in krīṇāti), is a Bhojpuri form2, and is also found in Bengali. The latter seems to be derived from the Hindi verb kharīdanā, of Persian origin.

In the first line, phrase caltī hai looks like the Hindi present participle. The subject of the sentence (nānā-nānī) is presumably treated as a feminine singular compound noun, rather than a plural. Thus there is gender agreement between nānā-nānī and the participle caltī, which is a distinctively Hindi rather than Bhojpuri feature.

At first glance, baiṭhehe in the second line sounds like a Hindi perfective participle with copula, i.e. baiṭhe hain (“they have sat”), which is the transcription provided by Mohabir (p. 14). However, I think this form is better understood as the Trinidad Bhojpuri -h- present in 3rd person (Mohan p. 151-152). This makes more sense contextually, since the entire song seems to be in present tense.

The pronoun merī (“my”) in the phrase merī nānī (“my grandmother”) is clearly from Hindi. In Bhojpuri, the only word for “my” is hamār.

In the first line of the refrain, I just love how the Hindi/Bhojpuri seamlessly gives way to Caribbean English: āge āge nānā cale, nānī goin’ behin’

For fun, here is a slightly different version of Nani Nani by Sundar Popo, with a more traditional “Indian” rather than “Caribbean” tune and rhythm.

Kaise Bani (supposedly first in 1969, definitely by 1979)

This song is rooted in traditional Bhojpuri folk music. The refrain is in Bhojpuri, while the rest of the song is in English. While Popo most likely penned the English parts himself, I have no idea how much of the refrain originated in India vs. the Caribbean.

—Refrain—

kaise bani, kaise bani, kaise bani, kaise bani,

kaise (how); bani (can I make)

How can I make, how can I make, how can I make, how can I make?

phulauri bina caṭanī kaise bani

phulauri (pholourie); bina (without); caṭanī (chutney); kaise (how); bani (to make)

Without chutney, how can I make pholourie?

—(The remaining lyrics are in English)—

A few observations:

Again, note the diphthongal pronunciation of ai in kaise, which is more similar to eastern languages (Awadhi/Bhojpuri) rather than Standard Hindi.

The -i ending of bani is consistent with the 1st person present/optative (i.e. subjunctive) tense of Trinidad Bhojpuri reported by Mohan (p. 146). In Gambhir’s treatment of Guyanese Bhojpuri, the -i ending may be used for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person subjunctive. (Gambhir p. 154). Both authors report that the infinitive is overwhelmingly formed with the ending -e (Mohan p. 180; Gambhir p. 171), meaning we should not consider the form bani to be an infinitive.

In the phrase phulauri bina caṭanī, the adposition bina (“without”) is modifying the noun after it (bina caṭanī, i.e. “without chutney”), rather than the noun before it. Thus, it is functionally a preposition, which is unusual since Indian languages (including Bhojpuri, Hindi, and Awadhi) overwhelmingly use postpositions (i.e. the adposition modifies the noun before it). Mohan confirms that in Trinidad Bhojpuri at least, bina in particular comes before the noun phrase that it modifies (p. 61-62)3, while all other adpositions come after the noun phrase. It is unclear to me if this is a peculiarity inherited from Indian Bhojpuri, but I will assume for now that it is4.

Ham Na Jaibe (1979)

This song is also rooted in Bhojpuri folk music, and is about a new bride’s apprehension at moving into her husband’s family’s house.

—Refrain—

ham na jaibe sasur ghar me, bābā

ham (I); na jaibe (will not go); sasur (father-in-law) ghar (home); me (in) bābā (father)

I will not go to my father-in-law’s home, O Father!

jiyarā jar gail hamār, bābā

jiyarā (life); jar (frozen); gail (has gone); hamār (my); bābā (father)

Life has frozen, O Father!

—Stanza 1—

roj roj sāsur dāru piyat he

roj roj (day-day [i.e. every day]); sāsur (father-in-law); dāru (alcohol); piyat he (drinks)

Every day father-in-law drinks alcohol

roj roj sās more lakṛī koñcat he

roj roj (every day); sās (mother-in-law); more (my); lakṛī (stick); koñcat he (pokes)

Every day my mother-in-law pokes [me] with a stick

—Stanza 2—

roj roj sās mor cijawā dikhāwe

roj roj (every day); sās (mother-in-law); mor (my); cijawā (the thing); dikhāwe (shows)

Every day, my mother-in-law shows the thing

dekhke sasur jiyā lalcāwe

dekhke (having seen); sasur (father-in-law); jiyā (life); lalcāwe (desires)

Having seen this, father-in-law desires life

—Stanza 3—

sās jhulāwe sāsurwā ke, bābā

sās (mother-in-law); jhulāwe (rocks); sāsurwā ke (father-in-law [acc.]); bābā (father)

Mother-in-law rocks father-in-law, O Father!

apnī godī sajariyā pe, bābā

apnī ([her] own); godī (lap); sajariyā pe (on); bābā (father)

Adorned on her lap, O Father!

—Stanza 4—

sasur pīte sasuiyā ke bābā

sasur (father-in-law); pīte (beats); sasuiyā ke (mother-in-law [acc]); bābā (father)

Father-in-law beats his wife, O Father

apnī choṭī jhopariyā mẽ bābā

apnī ([their] own); choṭī (small); jhopariyā (hut); mẽ (in); bābā (father)

In their small hut, O Father

—Stanza 5—

sasur pīte sasuiyā ke bābā

sasur (father-in-law); pīte (beats); sasuiyā ke (mother-in-law [acc]); bābā (father)

Father-in-law beats his wife, O Father

leke apni lakaṛiyā se bābā

leke (having taken); apni ([his] own); lakaṛiyā (stick); se (from); bābā (father)

Having taken his own stick, O Father

—

This song does not have any English, and appears to be a faithful adaptation of a traditional Bhojpuri song, perhaps from Sundar Popo’s childhood. While much of the song can be understood in the framework of Trinidad Bhojpuri, a few features stand out as unusual. Let’s list out the various features:

The pronouns ham (“I”) and hamār (“my”) are standard in Bhojpuri, where they are singular forms (in contrast to Hindi, where they would be typically interpreted as plural). Note also the lack of vowel ending in hamār; unlike Hindi, possessive pronouns and adjectives in Bhojpuri do not decline with the gender of the noun that they are modifying.

We also see another form of “my”, mor, in the phrase sās mor (“my mother-in-law”). This is not attested as a Trinidad Bhojpuri form in Mohan, or an Indian Bhojpuri form in Masica. However, we know that it is the standard form in Awadhi. In the song, sās mor is used for internal rhyme with the word sāsur (“father-in-law”).

Note the future-tense conjugation of jaibe. The usage of -b- in forming the future is confirmed by Mohan (p. 157), although interestingly she only gives the form jaib for first-person, rather than jaibe as in the song lyric. Interestingly, for nearby Sarnami, Damsteegt claims that the -e at the end of the 1st person future conjugation is emphatic.

gail (“went”) is the Trinidad Bhojpuri 3rd person past tense, with no vowel ending.

The phrase jiyara jar gail (“life has frozen”) appears to be an idiom5, but I’m not aware of an equivalent in Hindi/Bengali. The word jiyara (“life”) is most likely derived from Sanskrit jiva. I believe that the word jar comes from this.

Chadar Bheechaawo Balma (1980)

This is another traditional-sounding song, also about a newly married couple. The actual song starts at 1:15, after a prelude and introduction given by none other than the famous Indian singer Anup Jalota.6

—Refrain—

cādar bicāo balamā…caudariyā

cādar (sheet); bicāo (lay down); balamā (love)…caudariyā

Lay down a sheet, love

nīnd lage cal soye rahanā

nīnd (tiredness); lage (if feeling); cal (go); soye (sleeping); rahanā (stay)

If tired, we can remain asleep in peace

—Stanza 1—

more sasur jī ke dui dui mahalliyā

more (my); sasur jī (father-in-law); ke (of); dui dui (two-two); mahalliyā (palaces)

My father-in-law has two palaces,

sab se sundar hamār mahalā…caudariyā

sab se (of all); sundar (beautiful); hamār (my); mahalā (palace)…caudariyā

The most beautiful is our palace.

—Stanza 2—

more sasur jī ke dui dui palaṅghiyā

more sasur jī ke dui dui palaṅghiyā

more (my); sasur jī (father-in-law); ke (of); dui dui (two-two); palaṅghiyā (beds)

My father-in-law has two beds,

sab se sundar hamār palanghā…cadariyā

sab se (of all); sundar (beautiful); hamār (my); palanghā (sheet)…caudariyā

The most beautiful is our sheet.

—Stanza 3—

more sasur jī ke dui dui beṭawā

more (my); sasur jī (father-in-law); ke (of); dui dui (two-two); beṭawā (sons)

My father-in-law has two sons,

sab se sundar hamār balamā…caudariyā

sab se (of all); sundar (beautiful); hamār (my); balamā (lover)…caudariyā

The most beautiful is my lover.

—Stanza 4—

more sasur jī ke dui dui patohiyā

more (my); sasur jī (father-in-law); ke (of); dui dui (two-two); patohiyā (daughters-in-law)

My father-in-law has two daughters-in-law,

sab se sundar hamār jiyarā…caudariyā

sab se (of all); sundar (beautiful); hamār (my); jiyarā (life)…caudariyā

The most beautiful is my life.

—

Notes:

Again we see the usage of the possessive pronoun more (“my”), which is not particularly associated with the Bhojpuri language. This time, we encounter it with an -e ending in the phrase more sasur jī ke (“of my father-in-law”).

The Bhojpuri word dui (“two”) is the same as in Bengali, while its Hindi counterpart is do.

In the word beṭawā (“boy”), the suffix -wā indicates definiteness (Mohan p. 48) or diminutiveness, especially in vocative contexts (Mohan p. 51). The usage in the song here appears to be diminutive but not vocative. This is a distinctively Bhojpuri feature not found in Hindi.

The suffix -yā is used instead of -wā for consonant-final feminine noun stems (Mohan p. 49). In the song, this is seen in the words cadariyā, mahalliyā (“palace”), palaṅghiyā (“sheet”), and patohiyā (“daughter-in-law”). In all of these words, the suffix is probably being used to indicate diminutiveness rather than definiteness.

By leveraging a variety of resources, we were able to understand the meaning of almost every word in these songs! For me at least, this makes the act of listening to them all the more enjoyable. Evidently, the lyrics do not strictly follow the rules of Trinidad Bhojpuri language as described by Mohan. This is unsurprising, since Mohan specifically restricted her study to speakers who were both fluent in Trinidad Bhojpuri and did not have a functional knowledge of Standard Hindi. Sundar Popo, on the other hand, liberally mixed elements of Bhojpuri, Hindi, and English in his songs, more closely reflecting the linguistic environment of Trinidad than Mohan’s carefully controlled study.

To lay out these various linguistic influences explicitly, here is my attempt at categorizing the grammatical features we encountered by linguistic origin:

Features of Trinidad Bhojpuri inherited from Indian Bhojpuri

All of these features are attested in Mohan’s work, and to the best of my knowledge (which admittedly isn’t much), are also common features of Bhojpuri back in India. These features reflect the fact that Trinidad Bhojpuri was overall quite similar to its Indian predecessor:

Diphthong pronunciation of ai in the words jaise and kaise

Usage of u in words relating to “two”: dui and duno

The verb kin (“buy”), which is rare in Standard Hindi but common in Bhojpuri

The suffixes -wā and -yā to nouns to form diminutives or to give a sense of definitiness, as in beṭwā and patohiyā

The pronouns ham and hamār used in singular sense

Past tense ending -l, as in the word gail

Present participle forms piyat, koñcat

Features of Standard Hindi that are not found in any form of Bhojpuri

Both of these features are only found in one of the songs we listened to here - Nana and Nani - which I imagine was one of Sundar Popo’s most “original” compositions (i.e. not derived from a traditional folk song). Popo’s decision to use Hindi elements reflects the language continuum between the colloquial Trinidad Bhojpuri and prestigious Standard Hindi that existed in 20th century Trinidad (Bhatia p. 184-185). The Hindi features are:

The pronoun meri

Present participle phrase calti hai (I believe that the corresponding Bhojpuri phrase would be calat he)

Features associated specifically with varieties of Caribbean Hindustani

These are features that are well-documented in the literature on Caribbean Hindustani, and are thought to have arisen as a result of the unique koineization processes that occurred in the overseas colonies:

Alveolar pronunciation of Indic dental and retroflex stops (influenced from Creole English) - attested in Mohan, Gambhir, and Huiskamp for Trinidad Bhojpuri, Guyanese Bhojpuri, and Sarnami, respectively.

Usage of the verb form [stem]+e for 3rd person present indicative tense (probably originated from a widespread cross-language feature of colloquial speech in North India) - mentioned by Mohan, but described in detail by Gambhir.

The verb baiṭhehe, conjugated in the 3rd person present tense -h- form reported for Trinidad Bhojpuri (Mohan p. 152) as well as Guyanese Bhojpuri (Gambhir p. 118). It does not seem to be an accepted form in the Indian Bhojpuri present tense or participle phrases as reported by Grierson (p. 52).

The term phulauri refers to a snack food which is seemingly the same as the Indian pakora, but as far as I can tell (from the Wikipedia page as well as online recipes), it is associated exclusively with the Indo-Caribbean community. If the name and specific preparation really originated in the Caribbean, phulauri should be considered a uniquely Caribbean Hindustani lexical item not found modern Indian Bhojpuri or Hindi.

Features that are nonstandard in either Caribbean Hindustani or Hindi:

These are features of Sundar Popo’s song lyrics that, as far as I can tell, ar not explained by the grammars of Mohan and Gambhir, and are also not part of Standard Hindi:

The pronoun mor(e), which I think likely reflects Awadhi influence. While this could be due to an Awadhi-Bhojpuri mixing process that took place in colonial Trinidad, it also may have just existed in poetry and songs across the Gangetic Plain, given that Awadhi was once a major prestige language in North India. In my experience, it is common for Indian songs and poetry to preserve grammatical forms that are rare or even absent from the commonly spoken varieties of the language they are composed in, reflecting the complex spatiotemporal linguistic interactions in the subcontinent7.

The -be ending on the 1st person future form jaibe. Evidently, this form is neither recorded for Indian Bhojpuri (Damsteegt p. 119), nor is it attested by Mohan for Trinidad Bhojpuri. In both India and Trinidad, Bhojpuri tends to just use jaib. According to Damsteegt, the -be ending is, however, found in the 1st person future tense of Sarnami in emphatic contexts. It may be borrowed from Awadhi, where it is an accepted form (Damsteegt p. 119). It is possible that the same is true in Trinidad Bhojpuri, despite not being mentioned in Mohan’s work.

While we didn’t examine it above, another Sundar Popo song, Chalbo Ke Nahin, features the ending -bo in the 2nd person future form calbo. It is unaccounted for in Grierson’s account of Indian Bhojpuri, which lists -bī, -bis, and -bū (fem.) as well as -bē and -bah (masc.) as possible 2nd person future endings (Grierson p. 52). It is also not mentioned in Mohan or Gambhir for Trinidad and Guyanese Bhojpuri, respectively. Thus, it may either be a uniquely Caribbean form that these failed to sample in their studies, or an archaic form preserved in the song that traces all the way back to some dialect in India. It also may just be a grammatical error that Popo made up.

Overall, the most striking feature that marks all of Popo’s songs as distinctly Caribbean are his pronunciation of Indic dental and retroflex stops as alveolars. Additionally, his usage of -e and -ehe endings for the present tense may also reflect uniquely Indo-Caribbean linguistic developments. His incorporation of Hindi language elements reflects the Bhojpuri-Hindi linguistic continuum of 20th century Trinidad, although this type of language mixing also happens in India all the time when native and non-native Hindi speakers interact.

What explains the apparently unusual grammar elements in Popo’s adaptations of “traditional” songs? The generic origin story of these songs is that they were brought to the Caribbean in the 1830s-1910s by the primarily Bhojpuri-speaking indentured laborers from India. In subsequent decades, they were preserved and perhaps modified as they continued to be used for cultural traditions (specifically weddings). Sundar Popo, who listened to these songs as a child, used them for developing the chutney genre during the 1970s-80s. I can think of three possible explanations for why these songs contain elements not reported in accounts of Indian Bhojpuri or the Caribbean varieties:

The 19th century linguistic landscape of Bhojpur and surrounding regions was more complex than suggested by the sources I’ve read, especially when it comes to the language of song and poetry. Thus, phrases like ham na jaibe and tu na calbo may have always been a part of Bhojpuri folk songs, even back in India, and were faithfully preserved for decades in the Caribbean, all the way up to their usage in Popo’s chutney songs of the late 20th century.

The original Bhojpuri folk songs underwent morphological modification in the diasporic communities, picking up features of the newly developing koine varieties of Caribbean Hindustani. In this view, perhaps the forms jaibe and calbo were actual innovations of Trinidad Bhojpuri that flew under the radar of Mohan’s 1978 study, or were extinct by then due to language attrition.

Perhaps Sundar Popo simply misremembered the song lyrics of his childhood, and was not proficient enough in Trinidad Bhojpuri to know that certain forms like jaibe and calbo were ungrammatical. In the 1970s and 80s, there would not have been much of a societal feedback loop to correct for this anymore. When you’re one of the last speakers of a dying language, there simply aren’t that many people around to criticize your grammar.

One type of evidence that would help us a great deal in narrowing down these possibilities would be independent Indian recordings of these folk songs, which we could compare against the Caribbean versions and see where the lyrics might diverge. In fact, one might speculate that Sundar Popo simply copied contemporary Bhojpuri-language songs released in India, rather than actual remembering “authentic” Caribbean versions from his childhood. However, the available evidence does not support this theory. While it is possible to find Indian versions of Kaise Bani and Ham Na Jaibe on YouTube, they all appear to be covers of Sundar Popo’s versions! In both cases, the earliest Indian versions are from the early 1980s, a few years after Popo’s 1979 releases8. This makes it difficult to prove that these songs even existed in India prior to being introduced in the Caribbean! This phenomenon of cultural innovations in the diaspora making their way back to India is fascinating in its own right, and will be discussed in the next post.

The next post will also feature a discussion on the themes of Sundar Popo’s song lyrics, including his English-language lyrics, which we have purposely avoided so far. Stay tuned!

References:

Bhatia, T.K. 1988. “Trinidad Hindi: its genesis and generational profile.” In Language Transplanted: The Development of Overseas Hindi. R. K. Barz and J. Siegel (eds.), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz: 179-196.

Damsteegt, T. 1988. “Sarnami: a living language.” In Language Transplanted: The Development of Overseas Hindi. R. K. Barz and J. Siegel (eds.), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz: 95-120.

Gambhir, S.K. 1981. The East Indian speech community in Guyana: a sociolinguistic study with special reference to koine formation. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Grierson, G.A. 1903. Linguistic survey of India: Vol V. Pt. 2. Indo-Aryan Languages. Eastern Group. Specimens of the Bihārī and Oṛiyā Languages. Calcutta: Office of the superintendent, government printing, India.

Mohabir, R. 2019. Chutneyed poetics: reading diaspora and Sundar Popo’s chutney lyrics as Indo-Caribbean postcolonial literature. Anthurium, 15(1): 4, 1–17.

Mohan, P. 1978. Trinidad Bhojpuri: a morphological study. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan.

Gambhir devotes 13 pages of his thesis (p. 224-237) on this “e form,” examining its usage across multiple Indo-Aryan languages including the overseas varieties. He writes that although Hindi overwhelmingly uses a participle for the present indicative tense, “the e form had, and, it seems, still has a strong ground in the speech of the lower echelons of Indic society…It was thus such a pervasive use of the e form in Hindi dialects and its passive knowledge in the Bihari dialects that this form emerged so important in the Guyanese Bhojpuri verb system” (p. 236).

Hindi does have a version of this verb - kīnanā. I personally don’t think I’ve encountered it before. Indeed, the McGregor dictionary entry notes that it is “reg. (Bihar.)” - i.e. a regional variant from Bihar, the state where Bhojpuri is spoken.

In Hindi, I have found at least one song which features the phrase bin tere (“without you”), as opposed to the more common tere bina.

I looked up the phrase jiyara jar gail online, and the closest thing that comes up is the phrase jiara jari gaile as part of the name of a song sung by Mohammad Rafi for an Indian Bhojpuri film called Balam Pardesia released in 1979 - intriguingly the same year as Popo’s Ham Na Jaibe.

This was one of several cultural exchanges between Indian and Caribbean artists in the 1970s and 80s. We will discuss these interactions in the next post.

For example, the pronoun mor is also found in the Bengali poetry of Tagore, as in the line dui āñkhi mor kore col col (“my two eyes become tearful”) in the poem Tumi Jokhon Gān Gāhite Bol from the Gitanjali. However, mor is not used in standard spoken Bengali, which only uses āmār (singular) and āmāder (plural).